3 years, 6 months, 12 days

I would write “I’m back” here, only I’ve essentially written that many a time and not quite followed through. This is my first post in three and a half years. Three years, six months, and twelve days. There’s a pleasing symmetry to that. It’s incredible how much my life has changed in that time.

For one, I’m married now! My wife Rubi and I had our one month anniversary two days ago. Seeing the date of my last post on this blog (July 19, 2017), two things come to mind: I was already in love with Rubi, and we hadn’t started dating yet. She told me she had feelings for me four months later. We were long distance for another three years, including a brutal stretch of 13 months without seeing each other because of COVID travel restrictions. We got through that, and she makes me happier then I knew I was capable of being happy. When I last posted, I wasn’t even dating Rubi yet. That’s wild to think about for me. She’s my best friend, and I have trouble remembering what life was like before we were in love.

Another, much less happy thing comes to mind when I see the date of my last post. It was one year and three months after the death of my mom. If there’s any one thing that caused me to cease updating this blog, it was that. I tried in vain to post through the haze of my grief, but it didn’t work. My mom was such an inspiration to me as a writer and so much of writing became painful for me when she died. I didn’t give it up entirely, but writing about movies became impossible for some reason. I spent the first three years after my mom’s death figuring out the vocabulary for my own grief. Once I had it, I realized I needed help.

My last post was seven months before I started seeing a counselor who specialized in grief. My counselor, Caroline, ended up helping me come to terms with my mom’s death and then so much more. I ended up going to sessions with her for two and a half years. I came away from those sessions with a profoundly better understanding of myself, and of how to cope with grief and anxiety. Grief therapy isn’t easy. It can’t be. EMDR sessions could feel like running a marathon in wet sand. But I always came away with a sense of progress, that the terror I dealt with (grief had caused me to conflate sadness and fear in ways that made me repress any and all negative feeling in a profoundly unhealthy way) was manageable, that I could make it cease to be scary. Grief had made sadness terrifying to me. Therapy helped me learn how to feel sad again, which in turn helped me feel happy again.

I can’t describe how happy I am right now. I’m married to my best friend, and after years of long distance we are building a life together. I spent so many years afraid of the future. I look to my future with Rubi and I feel such joy.

Rubi and I live in Baton Rouge, Lousiana now. Life has a normality to it that I never thought I’d feel again. And this week, I started missing writing about movies again. I’ve missed it plenty of times before, but it’s been a long time since I felt that tug of inevitability that I used to feel, the sense that I had to write about movies again, the sense that kept me coming back to this blog for six years. I don’t know what I’ll write about yet, but I can feel that gentle vibration of words that need to be seen again.

So much has happened in three years. There will always be a gap between this post and the last one, and that gap will always represent a journey that I undertook, one in which I learned to cope with grief, one in which I fell deeply in love, one in which the love of my life endured literal years of separation and distance, one in which we finally joined our lives together. And along the way, through love and healing, I realized how much I needed to write about movies again. I’m back.

An upcoming blog feature, and a Blindspot update

So I’ve still been watching my Blindspot list. I’ll try to have my review of A Brighter Summer Day and The Piano up this week.

With that out of the way, I’m going to dive into a new project I’ve been wanting to try for a long time, in which I watch a slate of Best Picture nominees and decide for myself which one was the best. I don’t have a name for the project yet, but I do have a year that I’m starting with, and it’s… 1949.

As I use the “year the films came out” definition of “Oscar year”, here are that year’s best picture nominees:

All the King’s Men (winner)

Battleground

The Heiress

A Letter to Three Wives

Twelve O’Clock High

Of these I’ve only see All the King’s Men, so I’m looking forward to parsing through this year. I’ll try to have this done sometime in August and hopefully make this a monthly feature.

Peace and love and all the best!

I want to save you from your sorrow (on epiphanies in all their forms)

This started out as a plan to list a bunch of scenes of a certain type that I am fond of and turned into an personal treatise on beauty, grief, and grace in art. I don’t know how I swerve from talking about Labyrinth and Lost into Sufjan Stevens and Flannery O’Connor, but hey, that’s writing, isn’t it? I considered not publishing it, but this post is why I’ve taken so long to return after announcing my return, so I’m not gonna NOT publish it, am I? Regardless, I hope you get something out of it.

She is standing, defiant, in the face of a being of unknown power. He has her brother hostage and has thrown a multitude of tests at her to prove her worth at getting him back. And then, at the end of it all, he simply decides to ignore them and keep the child. Then she says, with the sudden clarity, of sunbeam breaking through a cloud, “you have no power over me.” His world falls to pieces, and her brother is saved.

That moment in Labyrinth made me love epiphanies in art. Sure, it’s on the nose. But as a seven-year-old this moment was monumentally satisfying; that a character trapped in a world with seemingly no escape realized, all at once, that the secret to defeating it was far simpler than she’d imagined; that this whole world was essentially her own creation and that she was the only one with power (forgive me for undoubtedly getting plot details wrong; I’m writing this from how I remember it from childhood).

Epiphanies can be a character’s or my own. Epiphanies can be Chihiro discovering Haku’s name all at once as they fly, or they can be me, realizing as I watched Spirited Away that I’d never seen a movie so perfectly meant for me before. Epiphanies can be Gabriel Conroy realizing he will never be able to love his wife the way Michael Furey did, or me reading The Dead for the 15th time and discovering a passage that is just perfect, whose perfection had eluded me the first 14 times. Epiphanies in art are wonderful, capable of delivering joy and heartbreak in equal measure, as utterly clear when they happen as they are nebulous to describe.

Lost had been much better than I’d ever imagined it could be. It was spellbinding from the first episode and gripping for nearly every moment after that. The season’s penultimate episode was called Exodus, Part 1, and it ended on a moment that felt like a prayer. A small handful of the show’s characters have decided to try to find help by sailing off on a man-made raft. The sequence where the raft departs is unlike anything I’d seen from any work of art before it, a dialogue-free sequence that represented a culmination of at least half a dozen storylines, concocted and depicted feverishly by Carlton Cuse and Damon Lindelof. The departure of the raft was a single act that was as weighty for its literal implications as its symbolism. It could only have worked on TV, with the medium’s unique ability to weave longform narratives by breaking them up into hourlong chunks, mingled with the visual beauty of Jack Bender’s direction and Michael Giacchino’s gorgeous music. It was a moment of grace like few I’ve seen on TV since. It was transcendent in a way that that word is very rarely used: it opened my mind to the possibilities of TV as a storytelling platform, but did so in a way so graceful and perfect for this specific show that I knew that a moment this good would come again very rarely. Indeed, I’ve watched and loved a lot of TV since this moment, including many shows that were much more consistent, more tightly written, less haphazard and frustrating than Lost became. But has there ever been a moment on television, before or since, that was so simply beautiful? There is grace in beauty, in concocting it out of parts that add up to something that completely transcends their sum.

I think a lot about the concept of grace in fiction. Not strictly in a religious sense, though I can’t deny that my understanding of grace as a concept is through a Catholic filter. In that sense, grace is the acceptance of God. In that sense, grace is tied quite closely with epiphanies; in Catholicism, the Epiphany is the celebration of the revelation that baby Jesus was one and the same as God.

Which is all to say that my religious upbringing no doubt set the table for this concept that so fascinates me in many ways beyond religious. And I’m not alone. The concepts of epiphanies and grace enrapture short story writers. The short story is really the perfect format for stories about epiphanies and grace. Their brevity prevent excessive exposition and usually require a fairly intense study of a single character. It helps is a character arrives mid-conflict and, in the story’s final act, is forced to make a decision about their lot. Most of us has read, Araby, the story by James Joyce that is so often taught for its clear, astute use of epiphany in the context of coming of age- in this case a young boy getting a harsh reality check about how life can let you down.

But epiphanies are more than just metaphors for adolescence. They way they tie in with grace make for my favorite works of fiction. The great Flannery O’Connor, master of Southern Gothic short fiction, made stories about epiphanies and grace a sort of obsession. Her vision of grace was violent and brutal. In her stories, grace presents itself at times inconvenient and epiphanies come too late to do much with them- staring down the muzzle of a serial killer’s rifle, or watching one’s mother collapsing and dying on the floor of a bus.

And it is in O’Connor’s stories that grace as a concept beyond a straightforward “person accepts or doesn’t accept God” choice began to resonate with me (ironically perhaps, as O’Connor was quite frank about her stories being parables). It was the horrific beauty of her presentation of epiphany that resonated with me. Many writers present characters who make grand realizations too late. In Flannery O’Connor, it really didn’t matter: the epiphany was the point. Whether a character might die or live mattered less than their discovery that grace was always hovering above them, waiting to be accepted or rejected.

These notions of life, death, and grace were all too abstract to me for most of my life. Of course, I had family members who passed away when I was a child, and when I was 18 my mother survived a harrowing medical ordeal involving a stroke and hospital-acquired pneumonia. But the blunt cruelty of death struck my family hard in 2016. In February, my grandmother died suddenly at 84. In April, my mom passed away at 59, just weeks after she discovered that the breast cancer she’d been battling for more than two years had spread to her spine.

I did what many people have done facing grief. I retreated. I stopped doing things I loved doing and found solace where I could. I turned to art. One album in particular I listened to a lot of was Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie and Lowell, which he wrote after his own mother passed away. There was one song on there that stuck with me: the album’s opening track, “The Only Thing”. I’ve written about it before. After that essay, which I wrote a month after my mom passed away, I kept listening to “The Only Thing.” I wasn’t sure why this particular song, which wasn’t always my favorite off the album (for the record, it’s an immaculate album, and “Fourth of July”, “No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross”, and “John My Beloved” are all just about perfect songs). It’s scarcely comforting, addressing depression and overpowering sadness head on. There was something more than despair to it, though. And all at once, on perhaps my 100th listen to it some months ago, the bridge hit. And listening to the lyrics again, closer than ever before, I was overcome. You see, the song is, for the most part, a first-person account of grief, one that hits closer to my own experience than any other portrayal of it that I’ve seen or heard or read.

Should I tear my eyes out now? Everything I see returns to you somehow

Should I tear my heart out now? Everything I feel returns to you somehow

God if that isn’t how I felt for so many days. There is no vocabulary for grief in our culture. There’s nothing that prepares you for it. For so many months, these were the lines that resonated most with me.

And all this time I hadn’t realized a slight shift, a glimmer of hope, that occurs right in the bridge, in the very next line.

I want to save you from your sorrow

It’s a slight shift, in perspective. It doesn’t even change the voice. It is, and can only be, a voice of the departed, trying to comfort those left behind. It had taken me months to realize this, and now that I had I started bawling. This lyric is an epiphany, emerging as a slight burst of light in a song that is about darkness. And for me, at that moment, it was the sort of epiphany I had needed, a reminder of my own mother’s relentless positivity. How she’d want to save me from my sorrow. There are flashes of grace in life, and they carry an outsize importance to me now. I find them in art more than anywhere. In moments when there is a synthesis of narrative and beauty that I find overwhelming. In moments where a character discovers a strength they didn’t know they had. But most of all, I find it music, when words and melody create a soundscape of sadness and then, for a moment, reveal the light that is waiting, always waiting, to burst through.

Featured image source

Well this is going as well as I expected

For my first post back I was working on a long-form thing that is spiraling off into directions I didn’t expect. I mean I think/hope it’ll be good but it’s becoming one of those “gonna take a bit to finish” pieces instead of “let me churn this out over an hour or two”. So yeah, I’m back, and working on stuff. It’s just taking a bit.

I never said I was gone, but I’m back

Hey all. I haven’t updated my blog in three months. There are a few reasons for this. One, my struggles with my mental health are perpetual and some months I find it nearly impossible to juggle freelance copywriting with all the other writing I love.

Second, I’ve plunged into writing a novel, and it’s consumed the vast bulk of my extra writing time in recent months. I’ve never tried something this big before and it’s taken me this long to be confident that I can keep writing my manuscript while not neglecting this space that has been so important to me.

So I’m back, hopefully consistently and for a long time. Posts on movies and other stuff coming soon.

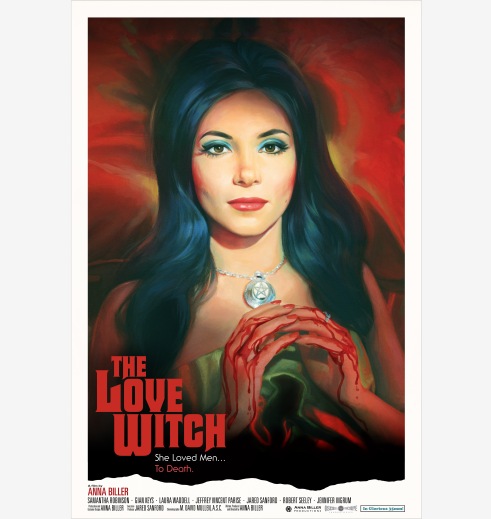

Blindspot 2017 February (March edition): The Love Witch

I wouldn’t normally put a film that came out last year in my Blindspot list. But sometimes a strange little indie that I overlooked the year it come out intrigues me with a premise so odd and a visual style so compelling and that I prioritize seeing them sooner than later. The Duke of Burgundy, The Assassin, and Blue Ruin are some other examples in recent year. And earlier this year, when I began seeing gorgeous stills from The Love Witch circulating around numerous blogs that I follow, I was hooked.

Simply as an exercise perfectly replicating the look and tone of 1960s camp sex comedies, The Love Witch is a remarkable achievement. Except for the fact that some characters drive modern cars, there is no way to tell that this movie wasn’t made in the 1960s on sight alone. It’s easy to imitate the look and feel of the 60s, but Biller goes a step further: her film has the look and feel of a soft-core exploitation film, but its story is actually a rather scathing commentary on modern, still relevant sexual politics.

The film opens with Elaine (Samantha Robinson), a young witch with a penchant for bright pastel outfits and a desire to find true love as quickly as possible, no matter the cost, driving to her new apartment. Right out of the gate, we learn that her first husband died, and despite her denials in her internal monologue, the list of suspects consists of her. She needs a place to lie low, and a fellow witch finds her an apartment which she has already had decorated to look like, well, a witch’s apartment.

The sets, costumes, and color scheme are all part of the profoundly immersive visual experience that is The Love Witch. The gaudy, popping colors make the film’s deliberately campy acting and dialogue fit right in. The plot, too, feels like fairly typical sexploitation camp, right up until the bodies start to pile up.

Elaine wants more than anything to fall in love, and she’s not patient about it. She uses love potions to win men over and enrapture them in a moment’s notice, but after sex they become overwhelmed with sadness, turning into blubbering messes. Then they die. Elaine hides the evidence and then tries again.

Anna Biller, who wrote and directed this film, has a sharp eye for satire. Elaine is a textbook naive romantic who simply takes her single-minded devotion to love to desperately absurd lengths. Elaine’s magic doesn’t seem necessary for her to initially seduce men; indeed, every single male character in the film views women as objects for entertainment, not people. But that her magic unlocks emotions that they were terrified to feel? And that those emotions literally kill them? It’s not subtle satire, but it’s very entertaining.

The Love Witch does run too long; there isn’t really much story here, just situations in which Elaine’s theories about getting someone to fall in love with her get tested and tested again until she can no longer cover up that she is, by any definition, a serial killer. Biller raises the stakes in the story by both having witches and magic be well-known commodities in society. That means there are inevitably anti-witch mobs as well, posited as the sort of misogynists who use the threat of rape and violence as a perpetual bulwark against women. And, well, Elaine isn’t really all that safe in her witch community either. We see early on that she resents the presence of Gahan, a warlock who it is hinted used his position as a mentor to Elaine to take advantage of her.

Early in the film, Elaine explains why she uses a seduction approach that involves pampering her targets’ insecurities and playing the part of a submissive vixen. “Men are very fragile. They can get crushed down if you assert yourself in any way,” she says. This worldview ends up getting flipped on its head many times over throughout the film. The statement remains the film’s thesis, but the context gets radically altered. At first, Elaine sees it as her path to winning true love; give a man sex, coddle his insecurities, no matter how puerile (her first target, a professor named Wayne, sobs that there are no women who are both smart and sexy enough for him to truly like), and voile, he will fall for her. That they immediately die might be a statement on how masculinity stunts men’s emotions and reduces their ability to interact with women to purely sexual terms. Elaine doesn’t need magic to get men to bed, but the potions she gives them to connect with her as deeply and purely as she hopes might as well be poison.

Biller grapples with some incendiary material here, all without ever deviating from the tone. A lot of that comes from how ripe 60’s exploitation films are for satire. Exploitation films used sex and nudity for cheap thrills; Biller uses them to ask tough questions about our culture’s views on love and sexuality. Biller doesn’t shy away from the ugly aspects of the genre; she uses satire to give them substance that an exploitation film wouldn’t provide. There is a genuinely disturbing scene where a mob threatens to rape Elaine. Biller gives the scene proper weight and sense of terror, and thankfully Elaine escapes. There is an ugly amount of sexual violence against women in TV and film, but Biller is at least saying something here about the threat of sexual violence that women regularly encounter, instead of simply trying to shock us.

The Love Witch is a sardonic, funny, beautifully shot film with a weary and pessimistic view of society, of masculinity, and of the world for a genuine romantic like Elaine. At the end of the day, she isn’t really judged for the bodies she leaves in her wake. And you know what? Films and TV shows ask us to forgive and like far more ruthless male serial killers all the time. The Love Witch simply asks us to understand how much Elaine loves being in love, and how unfortunate it is that she receives so little in return. Is that too much to ask? Or maybe I just fell under its spell.

Movies with Mikey: Princess Mononoke

I don’t normally link to videos here, but my favorite Youtube movie reviewer made a video about my favorite movie, and I’m not gonna sit here and not share that far and wide.

Blindspot January 2017 (March edition): Chimes at Midnight

Finally kicking off my 2017 Blindspot series! This one was a treat.

With the creation of Sir John Falstaff, Shakespeare made his greatest contribution to the grand literary tradition of supporting characters who are so entertaining that they upstage their stories’ protagonists. In Chimes at Midnight, he’s the star of the show, and it’s a glorious romp. When supporting characters shift center stage in any medium it can risk exposing them as more facile than we realized before. Some characters thrive in the wings and the shadows, bursting out from time to time but letting someone less fun but more substantial drive the story. But played and directed by Orson Welles, Falstaff proves a durable and thoroughly entertaining protagonist. Chimes at Midnight is not based on any one play, but rather pieces together several plays with Falstaff as the planet holding everything in orbit. I’ve seen few Shakespearean adaptations that so vividly capture the spirit and sense of fun in his work.

One risk of moving supporting characters to the forefront of any story is that they are generally more static, more easily defined by their characteristics than the leads. Welles doesn’t tame Falstaff or his overwhelming personality, but rather uses his penchant for simple joys and avoiding responsibility, for getting the most out of life with as little effort as possible, as a source of both conflict and eventually, an ending both befitting of Shakespeare and more respectful of Falstaff than the Bard actually provided (in Henry V, it is mentioned that Falstaff has died off stage, without him ever making an appearance).

Chimes at Midnight uses material from both Henry IV plays as well as Richard II and Henry V, eschewing much of the political theatre of the Wars of the Roses that those plays cover in favor of straightforward action; essentially, if it somehow affects Falstaff directly, it makes the cut. Falstaff couldn’t really care less about who is on the throne so long as he can sleep into the afternoon, put off paying his debts, and drink sack (sherry) from a seemingly bottomless mug. He spends his days and nights at Boar’s Head Tavern. It’s heaven to a jolly hedonist like Falstaff. The owner, Mistress Quickly (Margaret Rutherford) hovers around him asking him to pay his debts, but she’s in no rush to make a demand of it. The tavern overflows with booze, friends who chant his name, and of course Doll Tearsheet (Jeanne Moreau), the mistress who is always at her wit’s end with Falstaff even as she can’t quite muster true anger with him. Although Falstaff might like to give off the appearance of giving a damn, he does about a few people. For one, there’s Prince Hal (Keith Baxter), son of King Henry IV (John Gielgud) and heir to the throne. Falstaff’s fondness for Hal is more than just apparent. There’s an extended comic piece where Falstaff leads a group to rob some pilgrims heading to Canterbury. Hal thwarts Falstaff by posing as an armed guard, and when he gets back to the tavern he humors his mentor by letting him spin a tale in which he fended off an increasingly huge number of foes, before revealing that he had seen the whole thing. Falstaff’s reaction of feigned knowledge followed by joyful laughter is all we need to know about the depth of their friendship.

The duties of the throne eventually drive a wedge between Falstaff and Hal that cannot be removed. When the rebellious Duke of Northumberland and his son declare rebellion against Henry IV, Hal leads his ailing father’s troops into battle. Falstaff, known across England as a fearsome warrior, joins the war effort- or at least makes the appearance of it. The ensuing Battle of Shrewsbury is a brilliant directorial sequence, both as action and comic filmmaking. Faced with limited numbers of extras, Welles sticks the camera in the center of the action, which quickly becomes a whirl of mud, steel, and chaos. It’s a thrilling battle scene, intercut with shots of Falstaff, stuffed into a massive suit of armor, skirting around trees and trying to avoid being seen lest he have to actually fight. It’s apparent that his skills as a speaker are much more responsible for his reputation than his actual deeds on the battlefield.

The final act of the film sees Hal turn into Henry V, accepting his lot as king as his father’s health fails. When the coronation arrives, Falstaff is ecstatic, presuming that his surrogate son will have a place for him at his right hand. The final conversation between Hal and Falstaff is as stunning a sequence as the battle, without any threat of violence. It’s at once startling and inevitable; Falstaff’s life of avoiding consequences finally bites him, and it’s heartbreaking.

Chimes at Midnight is every bit the visual triumph that Citizen Kane was for Welles 25 years earlier. His expressionist tendencies hadn’t faded by the sixties. The castle halls of the scenes with Henry IV are ominous and remote. His throne seems perched atop a mountain of shadow. In contrast, the scenes in the Boar’s Head are delightfully grimy, the camera lunging back and forth between assorted characters, following the seemingly endless movement of its inhabitants. There is a splendid moment when Falstaff announces that he is going to put on an impromptu play, and the entire tavern circles around him spontaneously, and then in the upper floors several prostitutes burst out to watch as well, dressed only in bedsheets. The world of kings has no place for John Falstaff. But at Boar’s Head, Falstaff is beloved, and is perhaps the only person who can get everyone’s attention at once.

That Chimes at Midnight is available to watch at all is remarkable. It originated as a play that Welles performed in 1960. The play version of Chimes at Midnight was itself an adaptation of an even larger, more ambitious Shakespeare adaptation called Five Kings, in which Welles tried to condense all of Shakespeare’s plays about the Wars of the Roses into one production. Production and distribution of the film were rife with trouble, a common theme in Welles’s career. The film had a tiny budget, his actors were available for short periods of time, and Welles had to rush post production to get it ready to premier at the Cannes Film Festival (several characters’ voices are dubbed, some by Welles himself). It was never given wide release in the US, a fact often blamed (perhaps unfairly) on New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, who gave it a scathing review. It fell into obscurity before receiving a critical reevaluation in the 90’s, but it remained unavailable on DVD in the US until last year, when Criterion (God bless them, they do such incredible work) released a stunning 2-disc remaster of the film on DVD and blu-ray. It looks magnificent, and finally a film as good as any Orson Welles ever made is available to watch in North America. Chimes at Midnight isn’t just worth checking out; it’s essential.

Blindspot 2017 (FINALLY)

Hey all! So with a day and change remaining in February I’m finally getting to my 2017 Blindspot list. One note before we get to it: I never ended up getting through my last film on last year’s Blindspot, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels. It was a failure on my part; I watched the first half of it late one night, put the rest off until the next day due to sleepiness, and then I fell into a series of distractions where a week passed and I wasn’t able to finish it, nor could I muster the energy to back to the beginning and start over. I decided to instead to get to my 2017 list underway, and to return to Jeanne Dielman later this year.

Now, onto my 2017 Blindspot list:

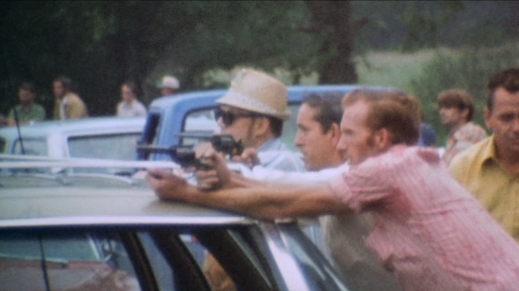

Finishing Blindspot 2016 #8: Harlan County USA

Harlan County, USA (Barbara Kopple, 1976)

The place is southeastern Kentucky, bordering Virginia. The time is the early ’70s, an era when there was turmoil to spare in the United States. The story is simultaneously specific and one that has been told time and time again. Since there was wealth to be had and labor to take advantage of it, the rich have exploited the poor. In Harlan County, USA, the poor are coal miners hoping to unionize, while the executives of the mining company they work for are willing to resort to increasingly brazen violence to stop them.

Barbara Kopple was just 27 years old when she lead her camera crew to Kentucky to cover the strike by miners at Brookside Mine, who were hoping for better wages, safer conditions, and benefits. They sign a contract to join the United Mine Workers of America. The Duke Power Company, which owns the mine, nixes the contract, triggering the strike.

Simply as an account of the chaotic events of the strike, Harlan County, USA is electric. Some of the footage Kopple gets is astonishing. The cameras sometimes pick up shouted threats from armed mercenaries and police, ordering her to stop filming. The methods used by strikebreakers, hired by Duke to manhandle the picketers and shuttle scab workers into the mines, grow increasingly violent. Kopple doesn’t provide a lot of names, but we grow accustomed to and even attached to a lot of faces. The wives and mothers of the miners are the primary force of the picket lines, defiantly standing up to guards who start by dragging them out of the lines and into jail cells into the dark, escalating to gunfire.

Kopple makes no attempt to remain detached. This is full-throated activist filmmaking, but unlike the work of Michael Moore, which can often turn into overwrought and didactic, Kopple keeps the cameras swiveling around, documenting whatever they can. One remarkable shot captures an infamous strikebreaker pointing his gun at the crowd. The shot ends up being evidence that forces the county sheriff to arrest the man, something he clearly has no desire to do.

Harlan County, USA is a reminder that progress has only ever been achieved through relentless effort, often in the face of seemingly overwhelming force and institutions uninterested in holding the powerful accountable. At one point, a miner at a demonstration in New York City (where they hope to tank Duke Power Company’s stock value) has a conversation with a cop, who is aghast at the conditions the miners face. The cop’s basic benefits and wages are modest, basic but compared to the miner, it sounds like a bounty.

The films ends with a mix of sadness, hope, and ambiguity. The miners get a contract, but only after one of the strikers is murdered on the picket line. They’re pleased, but one of the older miners point out that it doesn’t help those whose careers don’t have much time left to reap the benefits. And within a year, another conflict arises, putting the contract in jeopardy. The fight continues on, as it always has, as it always will.