Movie Review Roulette: Selection #8

First, the list:

Night of the Living Dead

Dark City

Raise the Red Lantern

Ratatouille

Children of Men

Yojimbo

Being John Malkovich

Millennium Actress

La Dolce Vita

Rear Window

Arsenic and Old Lace

Casablanca

Paths of Glory

Only Yesterday

The Conformist

The random selection:

I’m genuinely excited about this one. Millennium Actress is a top-five favorite film for me, and I haven’t seen it in a while.

Replacing Millennium Actress in the pool:

Singin’ in the Rain

Jupiter and Venus and The Tree of Life (Movie Roulette #7)

I have always been been kind of obsessed with stars. At night we can see thousands of celestial objects, larger than our world and more distant than I can comprehend. It took Voyager 1 thirty-six years just to exit our solar system. The next closest star after the sun is 4 light years away. It would take Voyager 1 another 40,000 years to reach that distance. All of us share our existence within a system of staggering size and scope.

The human story is, as far as we know, unique in our universe. The story of the universe began roughly 13.8 billion years ago, and from that moment immeasurable narratives burst. Our ability to learn those narratives beyond Earth is contained by the limits of our technology. But even then, slivers slip through space and time and find their way here. When I heard in May that scientists had detected what they believed to be an echo from the Big Bang, I was moved to tears. Another story had found its way to the only audience we know exists. It had taken almost 14 billion years and the rise of humanity and technology to a level capable of detecting it, but the story had made it.

We tend to look at the human story and the story of the universe as separate. One is ours, and one is… out there. But that is a matter of perspective. If you could look through the cosmos, through time, through the history of the universe, why wouldn’t you turn your attentions to a single family on Earth? Is their story not just as worthy of our attentions as any other story to be found in the universe? Echoes of the Big Bang are just one snapshot of the history of existence. And in The Tree of Life, Terrence Malick looks at a family through that lens. They are happening alongside the rest of the universe, and gently, slowly, we realize that that is a sort of miracle in itself.

Despite his reputation for “tone poetry” and whispered philosophizing, I think of Terrence Malick as one of our least ponderous directors. He doesn’t sit around looking for meaning and symbolism in minutiae. He’s not forcing us to listen to his pontifications. He simply observes what his characters do. All of his films have a detached quality, a sense that things are only moving as fast as the characters are willing to. Filmmakers rarely exercise this sort of patience. He lets his characters’ stories unfold at their own speed, and he makes sure it looks damn pretty. His Badlands, in which a film a teenage couple who go on a killing spree, makes no attempt to to provide an explanation for its characters’ actions. It simply shows them. Days of Heaven takes a similar approach to a plot that could just as easily have been made into a soapy Texas epic, a la Giant. Instead murder and romance take a backseat to a movie that views a storm of locusts as its climactic centerpiece. Why? Well, why not? To an impartial observer, the locusts would probably have more effect on your life than the melodrama going on around you.

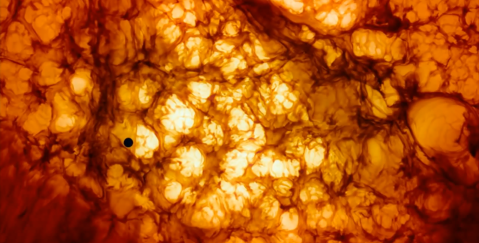

The Tree of Life opens on a scene of grief, as a woman and her husband learn that their son has died. We don’t learn how or why. The movie is not concerned with that. It witnesses their grief, like a bystander suddenly made aware that they are not alone by a cry of anguish. The following scenes are potentially confusing. Shots of the universe, of stars and nebulae and planets. Dinosaurs appear for a brief, strange interlude, only to be wiped out by an asteroid. We see shots of the microuniverse that surrounds us as well, cells and bacteria and blood flowing through veins. Yes, this might seem like the artiest of artsy asides by Malick. They confused me the first time I saw the film, even as I was awestruck by their beauty. When I saw the film again recently, I realized that awe was the point.

Consider how Malick treats the scale of all things. Nebulae, the massive interstellar clouds that give birth to stars, resemble cloaked figures here, almost humanoid. Planets are shown against stars, pinpricks in their appearance. Cells dividing and consuming one another appear like prehistoric sea creatures, seemingly huge and imposing. The scenes with dinosaurs are shot against the rivers and trees that seem recognizable later in the film. The sequence has a binding effect, tying all of history to the main story. A moment of personal grief resonates against the history of time. Whole histories of the world have come and gone several times over. Humanity is barely a blip on the scale of the universe. Think of Carl Sagan talking about the “Pale Blue Dot” photograph. There are so many stories to be told just on our planet, a planet that is so tiny compared to what surrounds it. Of all those stories, Malick has latched onto this one, this moment of human sadness. And he takes us back, back to the beginning, where we can learn where the sadness comes from.

The second act of The Tree of Life is a seemingly free-form depiction of the childhood of a boy named Jack O’Brien, the oldest son of the grieving parents. The parents in the first scene are Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien, played by Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain. Young Jack’s story is inter-cut with moments from the adult Jack’s life as he grapples with own grief from his brother R.L.’s death, and from his broken relationship with his father. The movie is not really so formless. It’s only as fluid as actual memories. So many films show adult narrators describing their childhoods with perfect, plot-point by plot-point detail. That’s not how memories work. When telling stories we inevitably fill in gaps. Good writers fill gaps with humor, with prose, with other anecdotes. But Malick isn’t concerned with filling those gaps. The Tree of Life shows us memories as we actually remember them. We don’t remember a perfectly plotted childhood. We remember specific times we were scared, when we laughed, when mass wouldn’t seem to end and staring at how the light came through the stained glass window was a surprisingly good way to pass the time.

My most vivid memory of childhood is this one time I walked out of a grocery store with my mom and into the sunlight, and then back into the shade of another building. The sunlight felt so good that I ran back into it and basked for a few more seconds, my eyes closed and my arms outstretched. I don’t remember what else I did that day, or even exactly how old I was. But that feeling of that sunbeam against my skin in that moment has never left me. If I was writing a novel, I might use that moment of truth to color my fiction. If I was writing a memoir, I might ask my mom for some more detail, to see if she remembers it the same way, or at all. The Tree of Life isn’t concerned with making a plot out of those moments. It cares more about how sunlight feels on your face.

We don’t get a traditional plot out of these moments, but we get a vivid picture of a childhood, of a boy grappling with a strict, at times terrifying father. Mr. And Mrs. O’Brien are less fully formed characters than towering figures in Jack’s life. That’s accurate. To a child, parents can seem life the Old Testament God, all powerful and occasionally confounding and even frightening.

Chastain delivers the films opening words via voiceover: “The nuns taught us there were two ways through life – the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow. Nature only wants to please itself. Get others to please it too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it. And love is smiling through all things.”

It’s tempting to see this quote as a thesis. Whoever wrote the film’s Wikipedia page uses the quote to quite literally categorize Mr. O’Brien as “nature” and Mrs. O’Brien as “grace”. While this interpretation of the quote is a bit too obvious and literal for my taste, it is not entirely off-base. Mrs. O’Brien loves unconditionally and shows it. Mr. O’Brien loves his kids too, but expressing it always plays second fiddle to establishing his authority. He reacts to even slight defiance from his sons with absolute rage. The film seems to make a point that a man as square-jawed and intimidating as Brad Pitt needn’t be so desperate to assert dominance over kids a third his size. Mrs. O’Brien is shown at first as an angelic figure, the advocate for her children, a saint in Jack’s eyes (one memory shows her literally dancing in the air, floating as she does). But she cedes to her husband’s authority, leading to a moment where Jack, full of fire and venom, rages at her that she never stands up to their dad when it counts. She is hurt. The scene ends. The emotion has been registered, and it’s time for the observer that is Terrence Malick’s camera to turn its eye to something else.

The movie isn’t trying to paint a depressing picture. There’s nothing here that suggests that the O’Briens live a particularly unusual or sad life. We do see Jack learning the wrong things from his father’s harsh lessons, taking out his confusions on his younger brother. We see a moment where he hurts his brother and immediately regrets it. He snaps out of his growing pains and back into reality. These are the types of moments that we remember in our own lives, from our childhoods. The times we wish hadn’t happened, that we would give anything to do differently, even years later. Mr. O’Brien says as much at the beginning of the film, as he mournfully regrets all the times he was needlessly harsh to his now dead son. Later on, we see a moment where an adult Jack calls Mr. O’Brien to apologize for an argument they had as adults, unseen in the movie. The movie isn’t trying to pinpoint the moment their relationship broke, or provide a cathartic moment of regret in the relationship between Jack and R.L. It’s a movie that hears a cry of grief at the beginning and traces the history of the source. It then settles in and starts to learn about these people. It takes a fleeting moment and humanizes everyone involved by showing them as they were, how they came to be. We don’t need every aspect of Jack’s relationship with his parents to be spelled out in melodramatic sequences to spoonfeed us their meaning. So much is said in a brief exchange when Jack tells his father “I’m more like you than her”.

The Tree of Life is particularly lovely, even by Terrence Malick’s standards. The spacescapes and microcosmos of the opening give way to scenes in small town Texas that are achingly beautiful without seeming to try. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki is one of the great film artists of our time. You probably last saw his work on Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity, which won him his first Oscar. If the Oscars knew a damn thing, Lubezki would have won an Oscar for this film too, as well his nominations for The New World, Children of Men and A Little Princess. His skill lies not in painting everything lushly, but in tailoring his work to the story at hand. In The New World, the story required smothering greens of the uncut 17th century American forests, of the senses being completely overwhelmed. In Children of Men, he filled the screen with sinister grays and always managed to find something interesting or menacing to linger on the edge of the frame. In The Tree of Life, Lubezki crafts memories in the little ways we remember details. The way light comes through a window, just a bit brighter than in reality, in child-eye view closeups that mimic how children study their surroundings, and in the dry earthinesss that seems embedded in every home in the neighborhood. “Hypnotic” is rarely the most exciting way to describe a film, but The Tree of Life induces a reverie in me. Its beauty is not just cosmetic, it is embedded in the movie’s soul, constantly reminding us what it feels like to remember something from years long ago.

The ending of The Tree of Life is one of Malick’s most audacious sequences, a vision of the afterlife, heaven, the end of time, whatever you wish to call it and perhaps all those things. Jack’s memories meld in one another as the dying sun consumes Earth, and he sees his mother as she was as he remembered her from his childhood, before he knew how to be cynical about her. He hears her finally, at long lost, accept his brother’s death, relinquishing her grief. Emotions are some of the most minute realities. They are deeply personal. But here Malick gives grief, love, acceptance, and forgiveness the scale they deserve. When we die, the emotions we evoke in those left behind are what remains of us. It’s why so many cultures place such significance on funerals. Funerals aren’t for the dead, but for the living. It’s how we begin the process of remembering the dead. What will happen when there is no one left to remember? The end of The Tree of Life seems to be Malick’s answer to that question. As the earth burns at the end of The Tree of Life, bits and pieces of everything still remain, unaltered from our memories, to finally provide closure for the scenes of pain that open the movie. This is a movie that quietly, gently, takes us across the entire span of existence before finding its final notes of love and acceptance at the end of time. In that sense it is Malick’s most human film, his meditation on the scale of individual existence. It’s easy to be cynical about the significance of any given person, of humanity itself, against the sheer size of the universe. But The Tree of Life considers the life of a boy in Texas to be as significant as any fleeting moment in a universe full of them. Its ending is the closest thing it has to a statement of its purpose. Despite criticism to the contrary, this is not a pretentious or pseudo-intellectual film. It is a spiritual one.

One last anecdote, and I’ll let you go. Recently I looked out my window in the wee hours of the morning. I noticed that Venus and Jupiter were incredibly close together, and for a moment I marveled at the novelty of it. And then I realized something: I wasn’t looking at two dots against the sky. I was on Earth, looking at Venus and then Jupiter behind it. The sky took on three dimensions, and I suddenly felt dwarfed by how small I was compared to what I was looking at. The scale astonished me. Here I was, one person staying up far, far too late, looking through our solar system, through hundreds of millions of miles of space, for the first time realizing with my naked eye how vast it actually was. The Tree of Life is like that. It isn’t simply gawking at the beauty of the stars and then dipping back to earth to tell the story of a family. It is in awe that they inhabit the same universe. It is about a family, yes, but the stage is all of space and time.

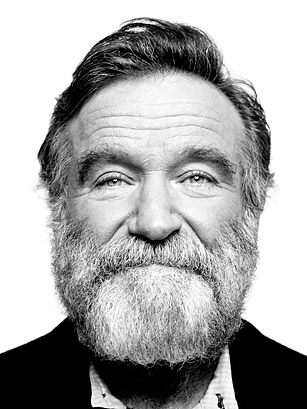

Rest in peace, Robin

I remember the thrill of his performance in Aladdin like few things from my childhood. I was five when that film came out, still at the age when I didn’t quite know or care about the difference between animation and live action. Animation seemed more real to me. It moved at the speed my mind did, created worlds like the ones I daydreamed about. And Aladdin’s Genie was THE unforgettable character from this world. His energy felt as alive as anything in a live-action movie. “Never Had a Friend Like Me” inspired both giddy awe and jealousy, as I wondered how I could acquire a friend like Genie in my own life. It’s easy for a film to pander to children. It’s difficult, truly difficult, to speak to them in their own language, which consists of an ever changing mix of colors and tones and feelings and, above all, heedless exuberance.

And so much of that was Robin Williams. Genie may have been visually created by animators, but the character needed Williams to provide the voice and, more importantly, the soul. When Williams put all his energy into a performance, it could sometimes come off as trying too hard. I like to think that he was simply moving too fast for any normal medium to keep up. Animation freed him from the shackles of performing in the real world. It was a perfect combination of character and performer.

Yes, Robin Williams was an essential performer to my childhood. I would grow up watching Jumanji, Hook, and Mrs. Doubtfire. I always felt a connection to his performances. Believe it or not, it was always something quiet and unspoken, an understanding of what he was trying to say as a performer. It’s too easy to say that he got typecast as playing a manchild in these films. It was the sense that was so much easier to convey through animation: that childlike sense of wonder and abandonment. I didn’t sense an adult playing dumb, but an adult trying to communicate to an audience that, for these films, was largely children. For me, he succeeded, more than any other performer.

He didn’t act in these films for lack of dramatic chops, after all. Time and time again he proved himself a stellar dramatic actor. Never more clearly than in Good Will Hunting. That is a film that has no business aging well, but it has thanks to the strength of its actors. Despite the screenplay Oscar that it won, Good Will Hunting’s script is far too full of indulgent flights of writerly fancy, verbose monologues that are exactly the sort of thing two twenty-somethings would write. The famous “baby seal” monologue exemplifies this. It’s the sort of writing that tries to convey too much on its own, as if forgetting that there will be an actor to do much of the heavy lifting.

But Williams nailed his monologue. Yes, the dialogue on its own is just all too neat a cutesy for me to buy being spoken by a no-nonsense Vietnam vet from Southie. It plays its hand- giving us a scene where Will is taken down a peg- too obviously. But Williams sells it. He takes a functional biographical laundry list and uses it to tell his character’s life story. Lines that would be awkward on paper are heartbreaking in his hands. It’s a deft and deeply human piece of acting.

The gulf between his chaotic comedic personas and his gentle dramatic ones was not as vast as it might seem. Either way, he trying to let the audience in to the world he was playing in, to let us share some of the fun. Sometimes that meant pouring all his energy into a performance, to try to make us happy. Sometimes that meant finding a person for us to latch onto in four minutes of dialogue, to reassure us that he would be there for us in this story. Yes, sometimes his performances could careen off the rails into a chaotic mess. But this is not judgment of an actor’s filmography. It is my attempt to come to terms with the immense sadness I feel at the death of a man I never met.

And I’m running out of things to say. Robin Williams is dead, apparently after committing suicide. It’s heartbreaking. I didn’t know him any more than any other celebrity who has passed away. But for an actor who made as many headlines for his failures as his successes, I feel a greater sense of loss right now than with any other celebrity’s passing in recent memory. I feel like I lost someone I knew. That, I think, was his gift as a performer, and perhaps why we who watched his films as children will remember him so fondly. At his best, he always made us feel included.

Edit: I accidentally cut out a line that left one of the paragraphs awkwardly phrased. This has been fixed.