Blindspot 2017 (FINALLY)

Hey all! So with a day and change remaining in February I’m finally getting to my 2017 Blindspot list. One note before we get to it: I never ended up getting through my last film on last year’s Blindspot, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels. It was a failure on my part; I watched the first half of it late one night, put the rest off until the next day due to sleepiness, and then I fell into a series of distractions where a week passed and I wasn’t able to finish it, nor could I muster the energy to back to the beginning and start over. I decided to instead to get to my 2017 list underway, and to return to Jeanne Dielman later this year.

Now, onto my 2017 Blindspot list:

Finishing Blindspot 2016 #8: Harlan County USA

Harlan County, USA (Barbara Kopple, 1976)

The place is southeastern Kentucky, bordering Virginia. The time is the early ’70s, an era when there was turmoil to spare in the United States. The story is simultaneously specific and one that has been told time and time again. Since there was wealth to be had and labor to take advantage of it, the rich have exploited the poor. In Harlan County, USA, the poor are coal miners hoping to unionize, while the executives of the mining company they work for are willing to resort to increasingly brazen violence to stop them.

Barbara Kopple was just 27 years old when she lead her camera crew to Kentucky to cover the strike by miners at Brookside Mine, who were hoping for better wages, safer conditions, and benefits. They sign a contract to join the United Mine Workers of America. The Duke Power Company, which owns the mine, nixes the contract, triggering the strike.

Simply as an account of the chaotic events of the strike, Harlan County, USA is electric. Some of the footage Kopple gets is astonishing. The cameras sometimes pick up shouted threats from armed mercenaries and police, ordering her to stop filming. The methods used by strikebreakers, hired by Duke to manhandle the picketers and shuttle scab workers into the mines, grow increasingly violent. Kopple doesn’t provide a lot of names, but we grow accustomed to and even attached to a lot of faces. The wives and mothers of the miners are the primary force of the picket lines, defiantly standing up to guards who start by dragging them out of the lines and into jail cells into the dark, escalating to gunfire.

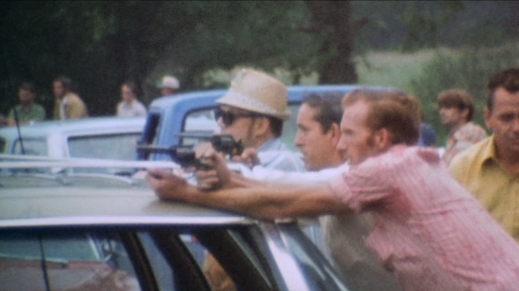

Kopple makes no attempt to remain detached. This is full-throated activist filmmaking, but unlike the work of Michael Moore, which can often turn into overwrought and didactic, Kopple keeps the cameras swiveling around, documenting whatever they can. One remarkable shot captures an infamous strikebreaker pointing his gun at the crowd. The shot ends up being evidence that forces the county sheriff to arrest the man, something he clearly has no desire to do.

Harlan County, USA is a reminder that progress has only ever been achieved through relentless effort, often in the face of seemingly overwhelming force and institutions uninterested in holding the powerful accountable. At one point, a miner at a demonstration in New York City (where they hope to tank Duke Power Company’s stock value) has a conversation with a cop, who is aghast at the conditions the miners face. The cop’s basic benefits and wages are modest, basic but compared to the miner, it sounds like a bounty.

The films ends with a mix of sadness, hope, and ambiguity. The miners get a contract, but only after one of the strikers is murdered on the picket line. They’re pleased, but one of the older miners point out that it doesn’t help those whose careers don’t have much time left to reap the benefits. And within a year, another conflict arises, putting the contract in jeopardy. The fight continues on, as it always has, as it always will.

Finishing Blindspot 2016 #5, #6, and #7: Yi Yi, Stalker, and The Battle of Algiers

Only two more and I’ll be ready to move on to my 2017 Blindspot!

Yi Yi (2016, Edward Yang)

Howard Hawks once defined a good film as having three good scenes and no bad ones. There are many, many good scenes in Yi Yi, and not a single bad one. Perhaps that’s why its 173 minute runtime feels a good hour shorter than that. Edward Yang, in this his last film before he died in 2007 of cancer at age 59, uses every minute of that runtime wisely. He paints a complete portrait of a family’s life over the course of a year, little by little, never rushing headlong into drama. Yi Yi is a bounty of a film, every scene rich with truth and feeling. Yang so fully understands these characters that he can simply show them being. In doing so he finds a truth that that I have long believed: that any life story, no matter how seemingly uneventful, is worthy of being told.

Yi Yi doesn’t adhere to any core plot other than ups and downs of regular life. Yes, it opens with a wedding and closes with a funeral, but these events feels matter of fact, instead of narrative bookends. Edward Yang leaves room for plenty of heartache, melancholy, amusement, joy, and ambiguity. He gives scenes time to breathe. There are few close-ups, but many long shots, or even scenes where he lets the camera look at the landscape as characters speak out of frame, or are tiny figures dwarfed by their surroundings. The closest thing Yi Yi has to protagonists are NJ (Wu Nien-jen) and his two children: his teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) and eight-year-old son Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang). The film opens at the wedding of NJ’s brother-in-law, A-Di (Hsi-Sheng Chen).

Weddings are a splendid way of introducing a big cast of characters (see: The Godfather), and the wedding here beautifully sets up the cast. A-Di’s bride is visibly pregnant, and family members argue about whether are right for each other. NJ’s mother-in-law is deeply melancholy and seems disinterested in interacting with anyone. An ex-girlfriend of A-Di’s breaks down sobbing that she should have married him when she had the chance. These might seem on the surface to be superficial touches at first, but each element comes back in to play. The film’s story runs along how people feel inside, about each other, and how they present those feelings. In this film, as in life, these feelings are fluid and sometimes far more important to us than we realize until we voice them. There’s a terrific moment when NJ runs into his first girlfriend, Sherry- they broke up decades ago- as she exits an elevator. They exchange pleasantries and part ways. Then she sudden emerges again into the frame and angrily tells him that he broke her heart and she never really got over it. Yang plays the moment seriously, because the moment is serious for Sherry. Neither does Yang linger on the moment. He recognizes that emotions aren’t fleeting, that this is story he can return to later in the film. Life doesn’t pause for feelings. They can be addressed in the flow of things. Life goes on.

Early in the film, the children’s grandmother has a stroke and falls into a coma. Throughout the movie, many characters use the doctor’s instructions to talk to her as if she were awake as a means of deep self-reflection. NJ’s wife, Min-Min (Elaine Jin), breaks down sobbing at not having more to say to her mother. Ting-Ting things she somehow caused her grandmother’s stroke and quietly asks for forgiveness. Yang-Yang is frightened to talk to her at all. All the while, life goes on for everyone.

I haven’t hooked you on this film, have I? Simply describing the events doesn’t capture its beauty. Watching Yi Yi is like getting wrapped up in a good, four-hour conversation, where there are highs and lows and raised emotions and tears and laughter and you come away feeling enriched, more knowledgeable about life, more attuned to humanity.

Stalker (1979, Andrei Tarkovsky)

To call Stalker existentialist, as many a take on the film I’ve see has, is tempting, but I think it runs the risk of being reductive (a term rarely used to describe existentialist art). Stalker is a masterclass of minimalist worldbuilding. The film takes place in a place called the Zone. For reasons no one can seem to explain, the Zone no longer follows the rules of space and time. It constantly changes, weaving a perpetual maze that traps those who wander in.are easily trapped and lured to their deaths. Only a select few people, known as Stalkers, can instinctively navigate the narrow, safe path to the end of the Zone, where there resides a room that will supposedly grant anyone their deepest desire.

Tarkovsky takes this premise, one that feels like it could easily make for a conventional adventure, and mines it for the effect the Zone has on its characters. As I said, his worldbuilding is essential. The film opens on the Stalker (most of the film’s characters go by titles, not names) lying awake in bed beside his wife and daughter. Their apartment is damp and spare. The world they live in is drab and heavily militarized. Tarkovsky doesn’t show us more than we could glean from the few moments we spend in this world, in this home, but it’s enough. Things are desperate. And still the Stalker risks his life- despite his wife Zhena’s desperate protests- to take people into the Zone.

The argument they have is telling. The Stalker doesn’t say he needs money. He doesn’t give his wife a reason for his leaving at all. There seems to be real love between them, so what gives? Why does he risk a job that drove his predecessor and mentor to suicide?

The Stalker sees the job as a calling, a blessing he can provide for others. In talking about the Zone with his customers- the Professor and the Writer-, he sounds almost priestly. The Professor and the Writer are more cynical, trading barbs with one another about their differing worldviews and speaking forthrightly (supposedly) about their hopes from this journey: the writer is hoping for inspiration, while the professor thinks his studies of the Zone might win him a Nobel Prize.

It goes without saying that none of these three men are entirely honest about their motives, whether they know it or not. Their journey through the zone, and their long conversations about the state of the world and their true desires, are reminiscent of a Samuel Beckett play. It’s in the world itself that Tarkovsky frames the story and builds mystery. He uses locations that look like they’ve long been there but are not quite recognizable. Dilapidated wooden buildings give way to beautiful, water-filled groves that look like tide pools filled with the remains of a ghost town. Tarkovsky vividly crafts a place that lulls you into a slumber of familiarity even though nothing makes practical sense and everything feels just a bit off. At one point, the three men end up in a concrete building that looks like swiss cheese. There is a phone on the ground and it rings, and the writer immediately picks it up as if it’s the thing he ought to do.

I can’t deny, the craftsmanship and tone of Stalker stuck with me more than the dialogue, but that’s not a knock on the movie. This is rare film where the chaos comes from deep within the characters themselves; the world around them seems just fine, at a glance, until you yourself look a little closer, and that’s when you realize where that chaos is coming from.

The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

Like Citizen Kane and Tokyo Story, The Battle of Algiers is one of those films with such a towering reputation that I knew quite a bit about it long before I watched it. Well, not the story and characters so much, but certainly how influential it is. It was screened by the Pentagon during the Iraq War and by numerous revolutionary groups. It was banned in France for five years after its release. That sort of history lead me to assume it was a sort of fly on the wall docudrama. What I didn’t expect was a film that manages to be both frank about the horror of war while still maintaining a passionate anti-colonial point of view, all without succumbing to preachiness. The Battle of Algiers is about the horror of violence begetting violence, yes, but there is so much more to it than sterile both-siderism.

This is not to say that the Gillo Pontecorvo picks and chooses which acts of violence are evil and which aren’t. There is no “good” in violence. No side in the film is depicted as deliberately villainous. But in battles between colonizers and their colonies, history has shown us that powerful nations will sometimes go to brutal lengths to subjugate those who don’t want to be subjugated. The sides in this story consist of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) and the government of France, which had occupied Algeria since 1827. Over the course of the film, both sides will kill scores of one another. Many unsuspecting, innocent civilians- French and Algerian alike- die in the crossfire. It’s all awful and, well, if there’s no morality in to any killing in war, there can be differences in motive for waging it. That is the subtle crux that Pontecorvo balances on throughout the film: as both sides escalate the carnage with no quick end in sight, is there at least a solution that has the plurality of moral weight?

The film opens in media res, as one of the FLN’s leaders, Ali La Pointe, cornered in a hideout with nowhere to run. The FLN’s resistance looks to be over. It then cuts back two years to the days before Ali joined the FLN, as the resistance is in its infancy. After he is recruited, he soon joins the ranks of the group’s leadership. Pontecorvo is matter-of-fact about their operations, as they carry out guerilla killings of police in broad daylight. Pontecorvo doesn’t glamorize the FLN or their actions; this, he seems to be saying, is how revolutions operate. He doesn’t shy away from the violence, nor does he sympathize with the occupying power. His sympathies are largely reserved for the civilians who end up inevitably caught in the crossfire. The French police chief has an apartment building blown up one night, killing numerous civilians, including children. As the survivors pull bodies from the rubble, it’s one of the few times Ennio Morricone’s music turns mournful.

That attack leads to greater violence from the FLN, who start bombing civilian establishments in retaliation. The police respond by calling in an elite paratrooper unit, lead by Col. Mathieu (Jean Martin). Col. Mathieu is cold and merciless, and makes it clear that he will use any methods he deems necessary to put down the rebellion. As newscasters celebrate Col. Mathieu’s arrival, they pointedly mention that he was part of the French Resistance. His most recent job? The war against Vietnam that preceded the USA’s own disaster there. The film makes pointed irony of a man who made his reputation fighting invaders is now leading them.

The documentary style, reminiscent of neo-realism, only even more convincing, gives the film a crucial sense of objectivity. This is not to say that Pontecorvo lacks a point of view; his style simply lets him make his points without being heavy handed. The film is anti-war, but also anti-imperialist, and it doesn’t feel contradictory. War is evil, but so is oppression, and sometimes only one side is guilty of both. God help everyone caught in the middle.