A brief, non-movie aside about why CNN is the worst

I still check CNN.com for quick news fixes. It’s a habit. Even though CNN has a godawful opinion section, and has ditched its partnership with Sports Illustrated for sports coverage in favor of the stinking sludgepit that is Bleacher Report, it is still a solid, go-to place for a quick rundown of events that have transpired in the last day, right?

Well, not really, not anymore. The “Breaking on CNN” meme (ie, joking that CNN only breaks years-old stories) ran out of steam months ago, but it was rooted in something very true: CNN’s coverage of Dzokhar Tsarnaev manhunt was woefully behind that of local news sources, and woefully inaccurate:

Anyway, when I checked CNN.com it this morning, this was the headline.

This is a terrible, terrible story, and my first reaction was, like I imagine it was for almost everyone, shock.

And then I looked at the presentation of the story, and I began to feel sick. Look at how the headline is structured: the subject of the sentence is not the victim, but the perpetrators.

And the perpetrators are not given any sort of concrete identity: they are simply “teens”. Coming off the heels of a much covered murder involving teens, this seemed oddly deliberate. Why not focus on the victim? And why is the age of the murderers so crucial?

But in just the headline and description, the word “teens” appears twice before the victim’s name, Delbert Belton, is even mentioned. That is followed by the kicker: a sentence mentioning how this is the second random murder this week committed by teens. All told, in that chunk of less than fifty words, “teens” are mentioned four times

This made it clear to me: CNN didn’t give a damn about Delbert Belton. They were manufacturing a trend. They were prepping for an onslaught of murder coverage, with teen murderers as the main draw.

Sure enough, CNN has obliged with a full course of murder-related stories today, including an obligatory opinion piece on the parental skills of teenage murderers, once again continuing the sickening trend of talking heads trying to diagnose killers from afar without any qualifications (which has led to widespread reporting of falsehoods like autism being linked to violent behavior), and ignoring the cold and less headline-friendly possibility that, sometimes, people just do evil things. Many more do good things. It’s part of humanity, but it doesn’t make for sexy headlines.

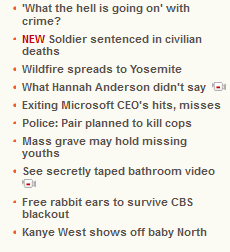

Yes, to some degree it makes sense that crime dominates news coverage. Overly positive news coverage can come off as treacly unless it pertains to acts of heroism or great human achievement. On the other hand, take a look at CNN.com’s top stories of the day:

That’s ten stories, half of which are related to murder, as well as one about destructive wildfires, and voyeurism story (complete with the chance to see the video yourself) for good measure. This is also excluding the top two headlines of the day: the Delbert Belton murder, and the conviction of Nidal Hasan for his killing spree at Fort Hood.

That’s ten stories, half of which are related to murder, as well as one about destructive wildfires, and voyeurism story (complete with the chance to see the video yourself) for good measure. This is also excluding the top two headlines of the day: the Delbert Belton murder, and the conviction of Nidal Hasan for his killing spree at Fort Hood.

Now, let’s look at that top story, the one with the headline “What the hell is going on?” (a quote from a CNN.com reader of Facebook). What do you think that story is going to be about? Because the story itself is actually about how crime is decreasing, and has been doing so for the last 20 years. The story also mentions, however, that 68 percent of Americans think crime is getting worse. And not once does the story even suggest the cause for the misconception.

I think that might have something to do with the fact that CNN is the kind of news network that takes its one story about the country’s decreasing crime rate and gives it the headline “What the hell is going on with crime”, and then plasters it alongside a never-ending buffet of stories about murder.

I called CNN the worst in the headline of this post. Well, isn’t Fox News worse, you might be wondering?

Yes, Fox News is vile, but it’s also already a punching bag. It doesn’t pretend to be anything but a shill for the far right, and they are called on this time and time again.

But CNN calls itself the most trusted name in news when its news has ceased to be anything but what CNN thinks can perpetuate a 24-hour cycle of mouse clicks and eyeballs. It’s what leads them to make minor but profound mistakes like dropping the ball on covering the Wendy Davis filibuster when it quietly took the internet by storm. It also leads to doing some things that are truly sickening in the name of dictating news coverage, like interviewing the kids of Sandy Hook elementary minutes after they escaped the gunman who murdered their classmates.

CNN is precisely the reason that Americans think our country is devolving into a bloodbath when in fact violent crime in this country is approaching historic lows.

Since CNN can’t say that crime is rising, which would be a blatant lie, they go a more surreptitious route, selectively reporting murders in a way that gives the false perception of a trend (again, it mattered less to them that an elderly man was murdered than that teens did it), and then reporting that trend as if it exists (when it doesn’t). They don’t simply report a murder: they dress it up as a trend piece, connecting it to another crime that has absolutely nothing to do with it.

And then CNN has the gall to mask a story that reports that violent crime is dropping in the context of its own readership being led to believe by their own coverage that it is on the rise- all this without once fessing up to their complicity in the whole ruse.

As I said before, the murders of Chris Lane and Delbert Belton are sickening. They are tragic by all measures. And they deserve better coverage than CNN is capable of giving them.

Edit: CNN.com has just now made the story about the crime rate drop its top story. Well, that’s nice, I suppose. Except the headline is still “What the hell is going on?” Couldn’t, you know, something that reflects the actual content of the story work?

Game of Thrones and the art of the monologue

Spoilers for Game of Thrones ahead.

Thinking back on the last two seasons of Game of Thrones, some of the most memorable scenes have been monologues. Monologues, hypothetically, are all tell and no show. To be effective, a monologue relies on both the writer and the actor for the speech to be more than just information to move the plot forward; they must tell us something about the person delivering the monologue, or shed new light on previous events, or otherwise do more than just pass the time. Done wrong, as The Walking Dead has done far too often, monologues become a lazy substitute for character building and drama, pretending that two characters engaging in extended whisper fights constitutes drama. But done right, as Game of Thrones does time and time again, a monologue can be as brutal or heartbreaking as any wordless action.

I’ve singled out three monologues from the show, each one delivered by a Lannister sibling, each telling a story about their father that ends up being much, much more than a simple tale.

The first is from the season one episode “Baelor”, the scene that likely won Peter Dinklage his well-deserved Emmy.

The information conveyed in this scene is important, yes. It tells us a cruel story from Tyrion’s childhood that helps us understand why he has embraced a sort of detached playboy mentality, and why he has such loathing for his father. One of the main criticisms of The Walking Dead is that it devotes so much dialogue, walls and walls of dialogue, to characters fighting about things we already know about without shedding new light on anything.

Here, in just a few minutes, a poisonous relationship is laid bare. It’s crucial for the show to establish just how far Tywin’s heartlessness extends. He is not just a bitter old man. He has no love lost for his own children, and the extent of his cruelty is frightening to imagine. This scene is a heartbreaking moment for Tyrion, but it also quietly establishes Tywin as an even more fearsome force than we could have known before. As expository dialogue goes, it’s hard to get more multi-purpose than this.

The second monologue is delivered by Jaime Lannister to Brienne of Tarth, his unlikely travelling companion with whom he develops an even more unlikely bond as she tries to deliver him back to the safety of King’s Landing.

In this scene, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau delivers perhaps the single best-acted moment in season 3, which is saying something. The show has become a murderer’s row of strong performers. Emilia Clarke earned a well-deserved Emmy nod this year, joining previous winner Dinklage, and nearly a dozen other actors in the show have an argument for consideration (Coster-Waldau, Michelle Fairley, Lena Headey, Charles Dance, and Natalie Dormer would be at the top of my personal list).

But his performance here tops all others, as I see it. Like Dinklage, Coster-Waldau delivers a personal anecdote, this one the first full account of the incident that gave him the title that haunts him to this day: Kingslayer.

There is a lot of history to parse through in this monologue. But Coster-Waldau delivers it with so much bitterness and regret that it feels like we’re intruding on his most deeply private thoughts, not listening to history lecture. This scene is heavy with catharsis: We’ve seen aloof Jaime, incestuous Jaime, attempted child-murderer Jaime, badass swordfighter Jaime, and most recently before this scene, suddenly one-handed Jaime.

But this scene peers a little deeper into the past of a man who has lived his whole life branded a traitor and coward. It finds that the act that defines him (to Westeros, at least; the viewers still know he tried to murder Bran Stark) is one that many others, perhaps almost all others, would have done in his situation; trading the life of a mad king for that of his father and an entire city.

Jaime is many things, and here we find that his devotion to his family exceeds most anything else. His glib line, “the things I’ll do for love,” when he pushed Bran out of a window seems less flippant now; here is a man who would kill a king and be branded a traitor rather than betray his own father. It doesn’t make Jaime a good man, but it makes him a much more complex one.

The third monologue is a quiet scene, so quiet that it could easily be lost in the chaos that surrounded it in season 3. The monologue is part of a conversation between Natalie Dormer’s Margaery Tyrell and Lena Headey’s Cersei Lannister. Margaery has been slowly making inroads within the royal family leading to her marriage to Joffrey Baratheon. She has been a cunning, delightful character to watch, and the scene in which she flirts with her sadistic, psychopathic fiancee by feigning an interest in crossbows and hunting was one of the most nerve-wracking scenes of the season, and ultimately triumphant for her, as she won the most unstable character in Westeros to her side.

In this scene, she is trying to make sweet small talk with her future mother-in-law and sister-in-law (oh Tywin, you and your heartless marriage arrangements). Cersei replies with a story about the origins of the Lannister family’s signature song: “The Rains of Castamere”.

This is a brutal little verbal beatdown by Cersei. Functionally, she makes it clear that she wants nothing to do with Margaery, and will always view her as an adversary. It’s a setback for Margaery, who had seemingly been effortlessly charming over her new family. And yes, reminding us of this song in such a vivid way ends up being a nice bit of foreshadowing for its truly memorable use in the next episode, when a performance of the song directly precedes the now legendary “Red Wedding”.

But consider how deliberate this show is. A warning this sinister does not apply to just the Tyrells; look at how the Starks were reeling all season after Rob lost the support of the Karstarks and was forced to go grovelling to Walder Frey. Even if you didn’t see the Red Wedding coming, this scene sets it up beautifully. “Game of Thrones” tends to use its largest plot upheavals in its 9th, penultimate episodes; this scene comes at the end of the 8th. For those who didn’t know the Red Wedding was coming, this scene is like a warning written in stone.

It’s a beautifully efficient use of about 90 seconds of dialogue. Like The Walking Dead, Game of Thrones is a very talky show. Unlike The Walking Dead, Game of Thrones’s dialogue is rich, evocative, and constantly moves the story forward. It’s aided by the very, very good cast, of course, and writers who know that the right choice of words, delivered perfectly, can alter the mood and change the course of a story as vividly as any other scene.

How “The Conjuring” seamlessly blended horror styles into the scariest film of the year

Spoilers for The Conjuring ahead.

Horror is actually surprisingly versatile genre. A film can ostensibly be horror while venturing into more straightforward dramatic territory (Let the Right One In/Let Me In), or action (the climax of 28 Days Later) or have healthy mixes of satire (Dawn of the Dead) or perverse (in the most twisted sense) comedy (Audition).

But when it comes to scaring you, most horror films adopt one of two approaches. Let’s call them “Confrontational horror” and “suggested horror”.

Confrontational horror bludgeons you with frightening, disturbing, and otherwise unsettling material. You can’t escape it. It’s confrontational and invasive. The Exorcist exemplified this approach, showing 1973 audiences that top-notch execution of potentially absurd material could scare the daylights out of people. Slasher films rely on this approach, as do zombie films. We know the adversaries in these films, and the knowledge of what they are capable of is the fuel for most of the scares.

Suggested horror does the opposite. It scares you with what you can’t see. It raises horrible possibilities and doesn’t let you off the hook. It plays off your imagination’s ability to create frightening possibilities. This approach was probably most famously used in The Blair Witch Project, although the thriller The Vanishing (the Dutch original, please) is my favorite example. The film makes no effort to mask its villain or his crime, but the sense of dread regarding the fate of his victim, and the hints the film gives to that fate without playing its hand, builds to a truly horrifying ending. Until that ending, not one scene in the film would allow you to peg it as a thriller out of context. The film hints, suggests, and slowly unravels, and grows all the more unsettling along the way.

In short: suggested horror scares us with the possibility of horror in what we don’t know. Confrontational horror scares us by not letting us escape from the horror we do know.

Upon watching The Conjuring again today, I was struck by how effectively the film uses both approaches. The first act is a masterful example of using what we can’t see to frighten us. The film’s exposition is tidy, establishing that SOMETHING malevolent is about, and targeting the Perron family (a man, woman and their five daughters at the center of the film’s plot). It introduces us to Ed and Lorraine Warren, experts in battling all things demonic, as the characters who’ll combat this malevolent spirit.

And then it begins to get scary.

The first third of the film is beautifully restrained. The spirit inhabiting the Perron’s house is alluded to, hinted at, through little details that are unsettling but that could still, hypothetically, leave room for a rational explanation. Throwaway remarks about a foul stench, Carolyn Perron’s odd post-coital bruises, the house’s clocks stopping at the same, are classic horror buildup: things we know indicate that something very bad is about to happen, but the characters don’t.

The beauty of the first act, and when the film starts to become really scary, is how the Perrons, one by one, realize that they are not alone. The film’s first instance of a member of the Perron family seeing the spirit in their house is elegant and terrifying in its method: it refuses to show it to the audience. The scene involves Christine, the middle of the five Perron daughters (a splendid little performance by 13-year-old Joey King). In the scene, Christine finally wakes up after being plagued by something grabbing her feet at night. The moment she realizes that it’s not her older sister Nancy is creepy enough. But the moment when her eyes fixate on a dark corner behind the door, unable to look away, is truly chilling. King sells the scene perfectly, demonstrating one of my favorite, underused tenets of horror: the fact that a character’s reaction to something horrifying can be as disturbing as seeing it yourself.

When Nancy gets up look in the corner to assuage her sister’s fears, the scene grows all the more terrifying, even though at no point do we expect whatever it is that Christine is seeing to actually attack Nancy. The terror of the scene is entirely that we believe that Christine is seeing something, even if neither we not anyone else in the film can. The horror is purely suggestion: we can’t see it… but we know it’s there. Christine can see it. We believe her. And whatever she sees is horrifying.

This splendid scene stands in contrast in style to the ending of the film, which is a full-blown phantasmagoria. The beauty of The Conjuring lies in how it builds from the spare, unknown horror of its first act to the brutal, inescapable horror of its last. Most horror films know only one volume. The Conjuring slowly increases its volume in increments that are almost imperceptible.

The middle act of the film is crucial in this regard. The attacks on the Perrons grow increasingly brazen and visual. Paintings and pictures are dashed to the floor. Carolyn gets locked in the basement and taunted. This culminates in one of the film’s two jump scares: the first visual revelation of the spirit to the audience.

All right, time for an aside on jump scares. Jump scares are not inherently bad. However, they are a component of horror, not an approach. “Confrontational horror” and “suggested horror” reflect styles that influence the entirety of a work. Jump scares are a type of scene. Films that rely too much on startling the audience quickly grow dull, since being startled is not the same as being scared.

However, being startled can be a component in scaring you. Drag Me to Hell, for example, used a neverending barrage of jump scares to help maintain its off-kilter, self-aware, darkly comedic tone. Every aspect of the film was so over the top, that jumps became part of the fun. The Conjuring uses jumps in a far more restrained way, more effective for purposes of scaring you.

Rather than jarringly slam the camera from side to side, James Wan gets a lot of mileage out of jumps that are not jumps at all, but creepy little set-pieces that work because they exercise just enough restraint, knowing that a pair of hands where none should be, or the realization that someone else in the room with you, can be terrifying.

In his scathing review of the film, critic Simon Abrams complained that The Conjuring relied too heavily on jump scares. I couldn’t disagree more. The film has a small handful of jump scenes, but in none of them is simply startling the viewer the method of scaring them. For example: the first big jump scare is the aforementioned first sighting of the demon within the Perron family’s home. The film stages the scene within the bedroom of the oldest Perron daughter, Andrea. It deliberately parallels the previous scene, presenting two daughters (the other, in the case, is the second youngest, Cindy).

It is here that the film uses its biggest jump scene. Unlike a typical jump scare, this one has us plenty scared already. Its similarity to the previous scene (which, as I mentioned, was terrifying without showing the audience anything) has us on edge again, well before the demon is actually sighted.

More than that, the reveal of the demon is a beautiful work of visual craftsmanship. A typical jump scare relies on throwing something unsettling at the screen without giving the viewer time to prepare themselves. In this scene, the film all but telegraphs the location of the demon at the top of the screen, hiding on top of a closet.

We know it’s going to be there. And that is terrifying.

The startling reveal of the demon is a coup de grace. It’s the icing of a very, very scary scene (which, it’s worth noting, is spliced together with Carolyn’s rather frightening search of the house’s basement, which is devoid of jump scares), not the entirety of the scares all on its own.

The final act of the film is all Grand Guignol, phantasmagorical horror, and it stands in contrast to the minimalistic opening scares. However, the film builds fluidly to its end, establishing its own sense of logic (the Warrens explain very carefully the nature of the demon, and how it plans to ultimately possess one of the family members) and following through. More than that, by the end of the film, we have been run ragged.

The final scene is aided by a splendid, physical performance by Lili Taylor as the now-possessed Carolyn. This may not seem like difficult acting, but it absolutely is. I have no idea how she found footing on the right side of the all-too blurry line between camp and horror, but find it she did. The ending of the film is a full volume blast of confrontational, loud, visceral horror. It is pure confrontational horror. There is no escaping it.

Could the film have worked as well as it did if it played at this volume throughout? I don’t know. I think it would have needed more of a sense self-awareness (a la The Cabin in the Woods or Drag Me to Hell). However, The Conjuring stands in stark contrast to those sendups of the genre; it is old-fashioned horror, earnest to its bones. And to maintain that face of utter seriousness in a movie that ends with so much excess, it was essential for The Conjuring to lure us into its world, rather than hold us above it. We had to believe this material. We had to be willing to let ourselves be scared without feeling the need to laugh about it at the same time. That is very, very difficult to do in these modern times, when it seems like every horror trick in the book has been played. And maybe they have. But The Conjuring demonstrates how polish and careful construction can make the funhouse look as good as new.